Morocco

Morocco

Morocco, with an estimated population of 37.14 million, is the fifth most populous country in the Arab region.[1] The population of Morocco is aging, mainly due to a steadily decreasing fertility rate reaching 2.3 births per woman in 2022 coupled with an increase in life expectancy to 74.9 in 2022.[2][3] The shift is visible in the drop in the percentage of the population below 30 years from 63.5 percent in 2000 to 50 percent in 2022.[3]

The World Bank estimates that poverty could have increased by 2.1 percentage points in 2022 due to inflation. The simulation suggests that the poverty rate could have increased from 3.4 percent to 5.5 percent.[4]

Since 2017, Morocco’s government adopted a range of measures focusing on increasing health spending, enhancing social protection programs, job creation, and supporting businesses.[5] As per the World Bank’s 2020 Doing Business report, Morocco introduced a series of regulatory improvements that mostly include facilitating the obtainment of construction permits, improving access to electricity, introducing e-payment of port fees, streamlining paperless customs clearance, automating the enforcement of contracts and reducing the corporate income tax (CIT) rate applicable to the taxable income ranging below MAD 1,000,000.[1][6] The ease of doing business score increased from 67.4 in 2016 to 73.4 in 2020.

However, after the sharp decline in growth in 2016, when GDP growth dropped from 4.3 percent in 2015 to 0.5 percent due to poor harvests, it picked up in 2017 up to 5.1 percent, to decelerate again. GDP growth declined to 2.9 percent in 2019[5][1] inhibited by a volatile and water-dependent agricultural sector and a stagnating services sector.[1] Real GDP grew 1.1% in 2022, down from the buoyant recovery of 2021 (7.9%).[7]

The government launched in 2008 the Moroccan Green Plan aiming to promote and modernize agriculture, stimulating exports of agricultural products and linking it more closely to industry. The implementation of the Green Plan, accompanied by favorable climatic conditions, has accelerated the rate of increase in agricultural activities from an annual average of 2.4 percent in 1998-2007 to an average of 6.3 percent in 2009-2018.[1] Nonetheless, the performance of the agricultural sector remained moderate compared to the target set by the Plan and the sector’s value-added started a downward trend in 2018, registering a decline of 5.4 percent. The contribution of the sector to GDP slightly dropped to 11.5 percent according to the latest statistics by Haut Commissariat au Plan. Agricultural value added fell 15% from 2021 due to the worst drought of the past 40 years [7]and it registered 10.7 in 2022 according to the World Bank. Similarly, the contribution of the sector to total employment also shrank between 2008 and 2021, declining from 40.7 percent to 34.5 percent, while the Plan was expected to create 125,000 jobs on average per year.[1][2]

The slow-down in growth was however accompanied by a growth in manufacturing exports – especially automobiles, electronics, and chemicals, and an increase of non-agricultural growth by 3.4 percent in 2019 (compared to 3 percent in 2018), mostly driven by an increase in the production of phosphates, chemicals, and textiles. GDP growth is projected to rise to 3.3% in 2023–24, driven by a recovery in agriculture[7]

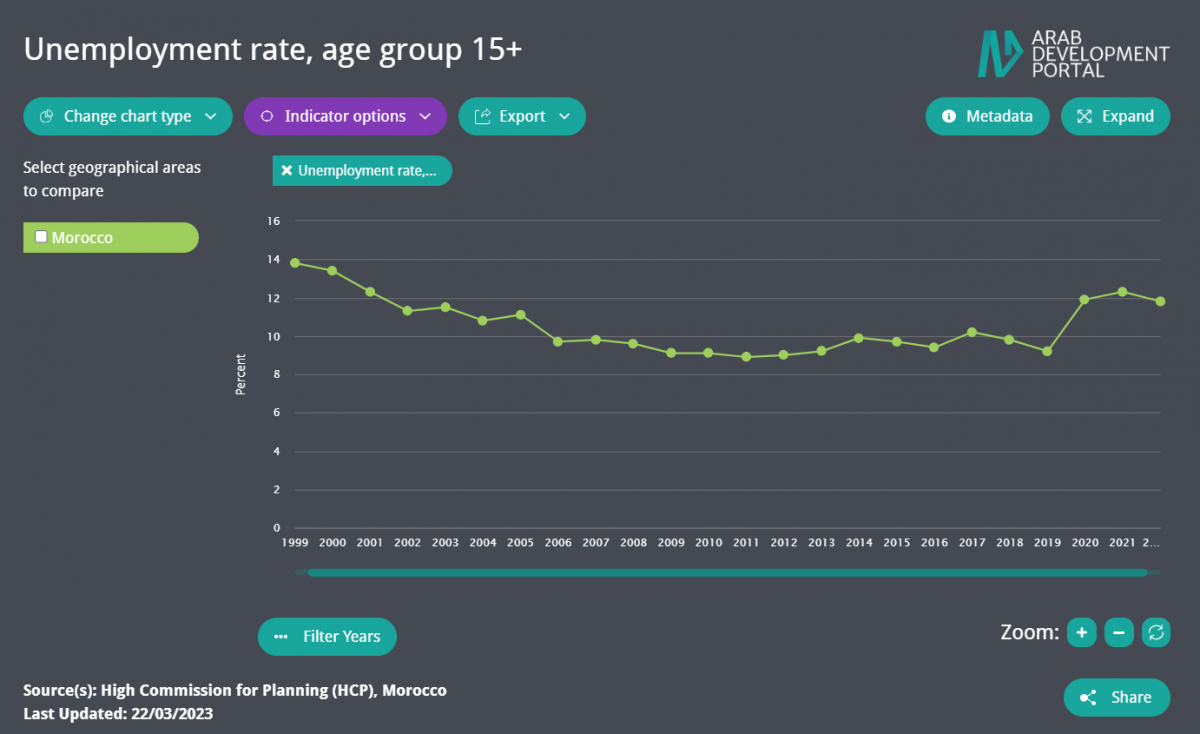

Inflation was very low, scoring 0.6 percent in 2019[5], it rose sharply to 6.6% in 2022 from 1.4% in 2021, driven by food inflation of 11% and higher commodity prices.[7] The unemployment rate declined slightly to 9.2 percent 2019 from 9.8 percent in 2018 then it increased to reach 11.8 in 2022. The rural-urban employment divide continues to be wide: unemployment in urban areas was 15.8 percent compared to 5.2 percent in rural areas according to the latest official statistics in 2022 [1] with urban youth unemployment reaching an alarming level of 46.7 percent in 2022.[1] The current account balance dropped to -1.7 percent of GDP in 2019 compared to -10.5 percent in 2017, mainly driven by the growth of manufacturing exports and the decline in the value of intermediate and consumer goods and energy prices. However, it registered -7.4 in 2022.[8][13]

According to the WHO, government health expenditure amounted to 2.61 percent of GDP in 2020, against the global 6.9 percent average. Consequently, out-of-pocket health expenditures reached 42 percent of current health expenditures, compared to a global average of 16.36 percent.[9] The number of physicians highlights public service deficiencies in the health sector with only 7.3 doctors per 10,000 inhabitants, compared with 17.2 in Algeria and 13 in Tunisia.[4]

By the end of 2018, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved financing the Precautionary and Liquidity Line (PLL) two-year arrangement for Morocco worth $2.97 billion. The arrangement aims to safeguard Morocco against unanticipated external shocks, support the economy’s resilience, and push for more inclusive growth.[5] In addition, fiscal reforms are key to help lower public debt, aiming at reducing it.[7]

Renewables have played an increasingly important role in Morocco’s energy sector, which stands out as a role model in renewable energy, ranking first regionally in the field of concentrated solar thermal power stations, producing around 32 percent of its electricity from renewable energy in 2019, reducing its imports of electricity by 93.5 percent.[10] By shifting toward cleaner energy sources, the country has become one of the largest renewable energy markets on the African continent, with a renewable capacity of 3.45 gigawatts in 2020. In 2022, renewable energies accounted for 16.1 % of Morocco's energy mix, excluding hydroelectricity. Morocco’s government has set ambitious targets, aiming at reaching 52 percent of the power generation from green sources by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050.[11][14][15]

This overview was last updated in November 2023. Priority is given to the latest available official data published by national statistical offices and/or public institutions.

Sources:

[1] Morocco Haut-Commissariat au Plan. 2023. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.hcp.ma/; https://applications-web.hcp.ma/DCN2022/CRegPIB14.html [Accessed 03 November 2023].

[2] The World Bank. 2023. World Development Indicators. [ONLINE] Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators [Accessed 15 August 2023]

[3] Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat. 2023. World Population Prospects. [ONLINE] Available at:

https://population.un.org/wpp/ [Accessed 03 November 2023].

[4] World Bank. 2023. Morocco economic monitor 2022/2023.[Online] Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/morocco/publication/morocco-economic-monitor-winter-2022-2023 [Accessed 03 November 2023].

[5] International Monetary Fund (IMF). April 2020. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/MAR [Accessed 22 April 2020].

[6] The World Bank. 2020. Doing Business 2020: Comparing Business Regulation in 190 Economies. [ONLINE] Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/688761571934946384/pdf/Doing-Business-2020-Comparing-Business-Regulation-in-190-Economies.pdf [Accessed 22 April 2020].

[7] The African Development Bank Group. 2023. Morocco Economic Outlook. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.afdb.org/en/countries/north-africa/morocco/morocco-economic-outlook [Accessed 03 November 2023].

[8] The World Bank. 2020. The World Bank in Morocco, overview. [ONLINE] Available at: http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/morocco/overview [Accessed 24 April 2020].

[9] World Health Organization (WHO). 2023. [ONLINE] Available at https://www.who.int/data/gho [Accessed 15 October 2023].

[10] Arab Union of Electricity. 2019. 28th Edition-Arab Electricity Magazine 2019. [ONLINE] Available at: https://auptde.org/en/latest-releases [Accessed 13 January 2020].

[11] Morocco World News. 2020. Morocco, Arab Leader in Electricity Generation from Renewable Energy. [ONLINE] Available at:

https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2020/02/293074/morocco-arab-leader-in-electricity-generation-from-renewable-energy/ [Accessed 24 April 2020].

[12] The World Bank. 2023. Doing Business database. [ONLINE] Available at: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/search/dataset/0038564/Doing-Business [Accessed 25 October 2023].

[13] International Monetary Fund. 2023. World Economic Outlook. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/SPROLLs/world-economic-outlook-databases#sort=%40imfdate%20descending [Accessed 24 October 2023].

[14] Atalayar. 2023. Morocco increases the contribution of renewable energies to its electricity mix and develops new clean energy projects. [Online] Available at: https://www.atalayar.com/en/articulo/economy-and-business/morocco-increases-the-contribution-of-renewable-energies-to-its-electricity-mix-and-develops-new-clean-energy-projects/20230713121500188154.html [Accessed on 03 November 2023].

[15] Statista. 2023. Renewable energy in Morocco - statistics & facts [Online] Available at: https://www.statista.com/topics/10486/renewable-energy-in-morocco/ [Accessed on 03 November 2023]

Data Highlights

-

The unemployment rate increased from around an average of 9.5 percent in the last years to reach 11.8 percent in 2022