Oil Price Developments: 2014-2016

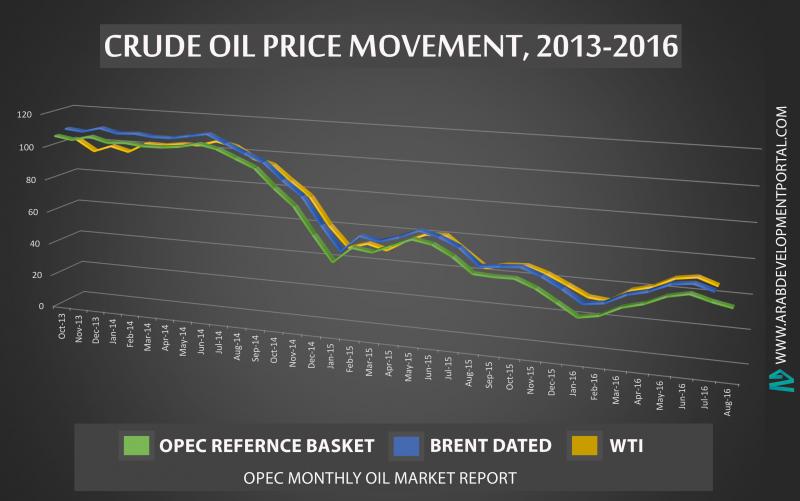

Oil prices started collapsing in mid-2014. Prices declined around 70%, falling from around $100/B[1] to approximately $30/B in early 2016[2]. Since mid-year 2016, prices rose to $50-40/B.[3]

Quite a lot has happened that would have a re-balancing effect on the markets. North American oil production has been declining for some time now. Iran has reentered the market, and oil production in Saudi Arabia and Iraq has increased. Nonetheless, production growth in Middle East OPEC has been partially offset by outages in Libya and Nigeria.

To understand the price crash, one has to examine a number of factors. First, the significant rise of non-conventional oil, i.e.: US Shale –Tight- Oil; Canada’s Tar Sands; and, Very Deep Offshore Oil (Gulf of Mexico, Offshore Brazil, North Sea and the Arctic). In the case of Shale Oil, the industry succeeded to introduce a new technology combining horizontal and hydraulic fractioning to produce oil and gas resources that were previously considered non economical to extract.

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimates in its Annual Energy Outlook 2016 that around 4.9mn b/d of crude oil was produced from tight reservoirs in the US during 2015[4], or approximately 50% of total US production during that year. The US Shale Oil industry grew rapidly mainly due to an increase in prices reaching a high $100/B but also as a result of increased credit facilities made available by banks to independent oil companies that led to the growth of the industry, improvement in infrastructure and logistical facilities (pipelines and tank farms), as well as the ample availability of a professional workforce. It is estimated that the average cost of Shale Oil production and other non-conventional oil is approximately $50-70/B. It is projected that the development of new non-conventional fields requires at least $55/B. As prices collapsed, oil firms and oil service companies have been obliged to cut down their investments and reduce their costs, laying the grounds for a supply shortage in the near future. Royal Dutch Shell cut 12,500 jobs over the past year[5] while the oil service firm Schlumberger slashed 16,000 jobs during the first half of 2016.[6]

To ensure a global market balance, OPEC has adopted a new policy since mid-2014. The global oil industry had previously relied on the major Gulf oil-producing countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, to adopt a flexible production capacity, during market shortages or surpluses. This entailed that major Gulf countries would act as swing producers, reduce production if there are excess supplies, or, increase output if there is a shortage. But since mid-2014, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Kuwait have refused to play this swinging role single-handily. They demanded that all producing countries, whether they are OPEC member states, or non-OPEC exporters, should participate and share the responsibility. They advocated that all the exporters should join in reducing production. The actual reason behind this policy shift was not clear. Some reports suggested that it might have been triggered by the political conflict between the GCC states on one hand, and Iran and Russia on the other. Other reports opined that there is a struggle for market share, as Iran has returned to the market, seeking to increase its production to the 4mn b/d and exports to 2.3mn b/d pre-sanctions level. Reports also suggested that the Gulf policy aimed to cap US Shale Oil production. The GCC countries have denied all these suggestions, stating that their policy aims to strike a balance in supply and demand to stabilize oil prices, and that for this to be achieved; all OPEC and non-OPEC exporters should undertake the joint effort.

As of 2016, there is a material re-balancing in supply and demand. OPEC production has been rising slowly; to around 33.4mn b/d.[7], but the incremental OPEC production in mid-2016 is approximately 700,000b/d, compared to an increase of more than 1.3mn b/d in 2015.Non-OPEC production is expected to drop by 900,000 b/d in 2016.

A fundamental reason for the price collapse is the record global oil storage level. Demand has remained relatively stable. BP Chief Group Economist Spencer Dale told the OPEC Review (6-7, 2016) in an exclusive interview that:

“This time oil prices fell not because demand was weak- demand growth in 2014 was pretty much in line with its long-run average. Prices fell in 2014 because supply was exceptionally strong.”

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates in mid-2016 show that the storage level has slightly surpassed 3bn barrels. This huge crude oil and petroleum products storage exerted great pressure on prices driving them downwards.

Oil firms continue to add to the storage in 2016, but less than in the past few years. Citi Bank estimated that global oil stocks increased by an average of more than 380,000b/d in the first-half of 2016, relative to the 2010-2014 first-half average of more than 480,000 b/d, and much below the first-half of 2015 average of more than 1,540,000 b/d. So far, oil firms continue to add to the stocks, albeit at lower incremental rates than previously registered. The re-balance of the markets would kick in when oil firms start withdrawing from the stocks. This is expected to happen by end-2016 second-half of 2017. “Although market balance is upon us, the existence of very high oil stocks is a threat to the recent stability of oil prices,” reports the IEA in mid-2016.

Another indicator of a forthcoming re-balance to markets is the number of drilling platforms that oil companies are purchasing. International Oil Companies have reduced investments and cut costs since the price crash. The purchase of drilling platforms is an indicator that oil firms are expecting higher oil prices in the near future. Data by the oil service firm, Baker Hughes, shows US active oil rigs have increased steadily since early summer 2016.

So how will these developments affect the Arab countries? It is well-known that the economies of the Arab oil-producing countries rely primarily on oil revenues. The collapse of oil prices has posed major challenges to these countries, as their revenues dropped by around 70%. To address this crisis, the governments have taken a number of measures. Public subsidies for domestic fuels were reduced. New public projects were either postponed or stopped. Civil service appointments were frozen or cut down. Some governments also resorted to domestic and foreign borrowing to alleviate cash liquidity problems. There have been few concrete moves to diversify economic resources away from oil. As long as the oil-producing countries remain totally dependent on oil income, their economies will continue to be vulnerable to the collapse in oil prices and suffer the consequences of a future oil price crash.

[1] OPEC Monthly Oil Market Report, [Online]. July 2014. Available at http://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/publications/MOMRJuly2014.pdf

[2] OPEC Monthly Oil Market Report, [Online]. February 2016. Available at http://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/publications/MOMR%20February%202016.pdf

[3] OPEC Monthly Oil Market Report, [Online]. August 2016. Available at http://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/publications/MOMR%20August%202016.pdf

[4] August 12, 2016. World tight oil production to more than double from 2015 to 2040. U.S. Energy Information Administration, [Online]. Available at http://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.cfm?id=27492

[5] Slav, Irina, July 5, 2016. Shell Warns of Further Job Cuts. Royal Dutch Shell PLC, [Online]. Available at http://royaldutchshellplc.com/2016/07/06/shell-warns-of-further-job-cuts/

[6] Wethe, David, July 21, 2016. Schlumberger Joins Halliburton in Calling Oil Cycle’s Bottom. Bloomberg, [Online]. Available at http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-07-21/schlumberger-posts-surprise-2-2-billion-loss-cuts-more-jobs

[7] OPEC Monthly Oil Market Report, [Online]. August 2016. Available at http://www.opec.org/opec_web/static_files_project/media/downloads/publications/MOMR%20August%202016.pdf

Dr. Walid Khadduri is a member of the Arab Thought Forum, Amman, and the Oxford Energy Club. He is a member and co-founder of the Arab Energy Club, 2009. Khadduri is a former Editor-in-Chief of Middle East Economic Survey (MEES).

The views expressed here are solely those of the author in his/her private capacity and do not in any way represent the views of neither the Arab Development Portal nor the United Nations Development Programme.