Trade

Trade, so far, has not played its potential role in enhancing sustainable growth and development in the Arab region when compared to other regions in the world. The majority of Arab countries still have a long way to go to advance trade logistics and reap the benefits of trade in services and digital trade.

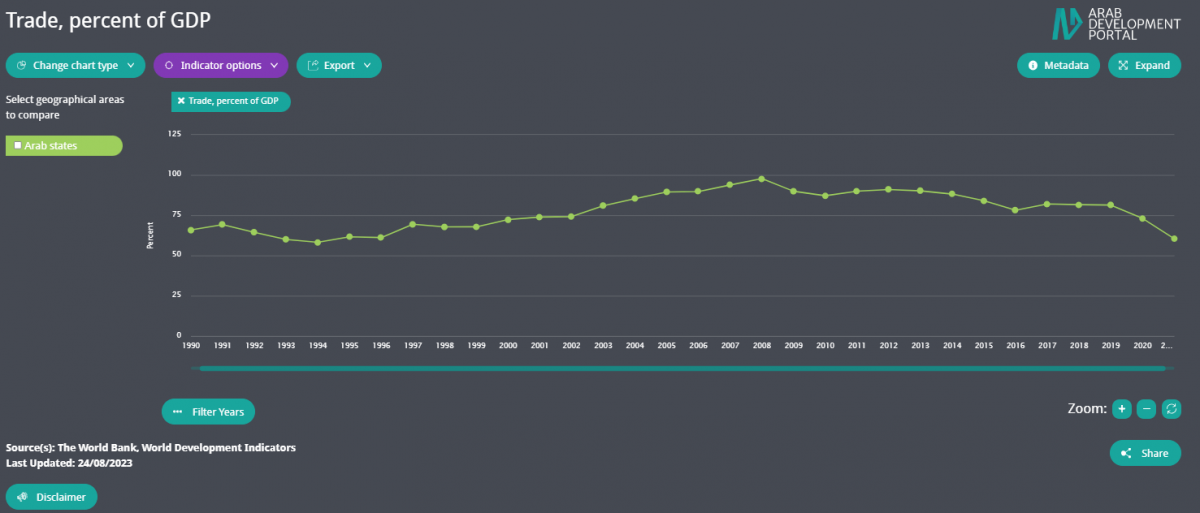

Trade openness indicators' latest available values (measured as the ratio of total trade to GDP) in the region range from more than 223.12 percent in Comoros and 166.57 in UAE (2020) to around 2.7 percent in Sudan in 2022. Differences in the size of the relevant economies and the indicators dealing with merchandise and services trade complicate comparing the region to the global trade openness figure of around 56.52 percent in 2021.[1] In the Arab region, trade in merchandise goods, namely oil, accounts for a major proportion of the trade openness indicator whereas services play a limited role. Trade openness is at 80.56 percent for the Arab region in 2022 but should have been higher given the small size of the Arab economies. [1]

Trade in the Arab region is significantly affected by the oil market: fuel exports made up an average of 67.97 percent of total merchandise exports in 2021 compared to a global average of 11.62 percent.[1] All Arab countries are net food importers even though food imports make up only 12.03 percent of total imports in 2021, compared to the global average of 8.43 percent.[1] The Arab countries have not tapped the potential of trade in services (e.g. in tourism, and transport), and are not highly engaged in world value chains[2] with limited integration of Arab economies in the global value chain (measured mainly by trade in intermediate goods).[3] and the relative absence of an Arab regional value chain should signal the need for a new setup in light of the disruption that happened to global value chains as a result of the impact of COVID-19.

Arab countries are members of several preferential trade agreements (PTAs) whether among themselves (e.g. Pan Arab Free Trade Area, Agadir, Gulf Cooperation Council, Arab Maghreb Union) or with developed and developing countries and groupings (e.g. EU, USA, Canada COMESA, MECOSUR).[4] There is high variation among Arab countries, where Jordan, for instance, is a member of a large number of PTAs, compared to Comoros and Yemen which are engaged in very few PTAs. The majority of such PTAs have remained confined to the removal of tariffs, and have not dealt with behind-the-border issues, illustrating the limited impact of PTAs in enhancing trade among Arab countries.

The socioeconomic implications of COVID-19 and the recent world economic crisis have likely curbed the role of trade in the Arab region, namely due to sharply reduced demand for oil, lock-down measures, and the slowdown in trade as a result of the world economic recession. Disruption of world markets is also affecting trade, via protectionist measures in net food-importing Arab countries. For example, Egypt imposed a ban on white and raw sugar imports for a period of three months starting June 6, 2020,[5] with the Minister of Trade and Industry citing low world prices during the pandemic and their potential to hurt the domestic industry (Egypt is a net importer of sugar) whereas in March 2023 the Minister of Trade and Industry announced a three-month ban on all types of sugar exports except quantities that exceed local market needs. [6] Other countries are likely to follow suit with ad hoc trade protectionist measures inspired by the flux in the world markets.

Service trade including tourism is being hit hard.[7] Tourism is a major source of foreign exchange and employment for a large number of Arab countries, including. Saudi Arabia (Hajj and Umra pilgrimage); and Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, UAE, and Lebanon (different types of tourism). According to the latest available UNSD SDG data (2019-2021), tourism direct GDP represented between 1 and 7.06 percent of GDP for countries with available data with some discrepancy in Arab countries.[8]

It is important to emphasize that Arab countries need to invest in trade logistics. Available indicators (e.g. trading across borders in the doing business measures confirm that Arab countries have a long way to reform their enacted trading systems. The doing business indicator (2020) for Arab countries on average put them in the rank of 118 among a total of 190 countries, with three Arab countries among the worst five performers globally. When focusing on the indicator associated with trade in particular, namely trading across borders, the rank deteriorates to 127 on average amongst 190 countries all over the world with two Arab countries among the worst five performers.[9]

Arab countries need to pay extra attention to digital trade given the expected role it is likely to play in the post-COVID-19 era, especially with the central role of ICTs and services and the digital infrastructure on which they grow. [10] Hence, additional efforts to upgrade related services (ICT infrastructure and digital financial services) are still needed[11] to ensure e-trade readiness. According to ESCWA’s Government Electronic and Mobile Services (GEMS-2022) Maturity Index, some sectors such as trade, industry, and tourism still need to do more to digitize their services.[12]

This overview has been drafted by the ADP team based on the most available data as of August 2023.

[1] The World Bank. 2020. World Development Indicators. [ONLINE] Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators [Accessed 24 November 2020].

[2] United Nations Economic and Social Commission for West Asia (ESCWA). 2017. Transport and Connectivity to Global Value Chains: Illustrations from the Arab Region. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.unescwa.org/publications/transport-connectivity-global-value-chains [Accessed 24 November 2020].

[3] Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2015. Participation of Developing Countries in Global Value Chains: Implications for Trade and Trade-Related Policies Summary Paper. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.oecd.org/countries/gabon/Participation-Developing-Countries-GVCs-Summary-Paper-April-2015.pdf [Accessed 24 November 2020].

[4] The World Bank. 2023. World Integrated Trade Solution. [ONLINE] Available at: https://wits.worldbank.org/gptad.html [Accessed 13 August 2023].

[5] EG24 News, Egypt. 2020. How does the ban on importing sugar affect local comapnies and marker prices? [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.eg24.news/2020/06/how-does-the-ban-on-importing-sugar-affect-local-companies-and-market-prices.html [Accessed 24 November 2020].

[6] Ahram online (english), Egypt. 2023. Egypt bans sugar exports for three months: Trade minister [ONLINE] Available at: https://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/3/12/492245/Business/Economy/Egypt-bans-sugar-exports-for-three-months-Trade-mi.aspx [Accessed 13 August 2023].

[7] World Economic Forum. 2019. Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Report 2019. [ONLINE] Available at: https://reports.weforum.org/travel-and-tourism-competitiveness-report-2019/regional-profiles/middle-east-and-north-africa/. [Accessed 24 November 2020], and World Travel and Tourism Council.2020. Economic Impact Reports. [ONLINE] Available at:

https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact [Accessed 24 November 2020].

[8] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2023.SDG indicators database. [ONLINE] Available at: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/dataportal/database . [Accessed 13 August 2023]

[9] The World Bank. 2023. Ease of Doing Business Rankings. [ONLINE] Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/businessready/doing-business-legacy [Accessed 13 August 2023].

[10] ITU. 2021. Digital trends in the Arab States region 2021. [ONLINE] https://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/md/18/rpmarb/c/D18-RPMARB-C-0002!R1!PDF-E.pdf [Accessed 13 August 2023].

[11] The World Bank. 2016. ICT use for business-to-business transactions, 1-7 (best). [ONLINE] Available at: https://tcdata360.worldbank.org/indicators/hf0d27aa9?country=DZA&indicator=3443&countries=BRA&viz=line_chart&years=2013,2016 [Accessed 24 November 2020].

[12] UNESCWA. 2022. Government Electronic and Mobile Services (GEMS-2022) Maturity Index Report. [ONLINE] Available at: https://ada.unescwa.org/sites/default/files/resources/government-electronic-mobile-services-gems-maturity-index-2022-english.pdf [Accessed 13 August 2023].

Data Highlights

-

The Arab region is outstandingly rich in oil and gas and the relatively low level of economic diversification leads to a persistent dependence on these commodities for growth.